Key Takeaways

- Being exposed to the traumas students bring into school every day can exact an emotional and physical toll on teachers and other educators.

- Research suggests that compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress is prevalent among teachers, especially those in high-poverty schools, and is a factor in their decision to leave.

- Educators and their unions are advocating for system-wide strategies to address educator well-being. "We don't need any more Band-Aid solutions," said one union leader.

Melissa Manganaro knew “something was off” by her sixth year as a school counselor. Manganaro loved her job, her students and her colleagues at Mountain View High School in Mesa, Arizona. But she was beginning to feel more anxious, tense, and fatigued.

Manganaro wasn’t really sure what was happening. She wasn't depressed, nor was she "burned out" exactly.

“I just felt my empathy was exhausted,” she recalls.

It wasn’t until she attended a session at a professional conference that her problem came more into focus.

The session focused on compassion fatigue, a term Manganaro wasn't familiar with. But what she learned opened her eyes and eventually changed her career path. She took a quick self-test at the session, and found out she was at “high risk” for compassion fatigue.

It made sense. Her trigger was listening to students who were in crisis. And, as a counselor, Manganaro routinely heard from teenagers about self-harming or suicide ideation. After these meetings, she would often break down.

“I was trained to discuss academics or career paths,” she says. “There is a social and emotional component to this work, but I'm not a mental health professional. So I was not prepared for this.”

After attending the school psychologists' conference, “I knew I wasn’t the only one.”

Compassion fatigue is the most widely used term to describe how educators internalize or absorb their students’ trauma to the point of emotional and even physical exhaustion. Classroom teachers, counselors, paraprofessionals, school secretaries all care deeply about their students—but it can come at a price.

Student mental health was on the national radar before the COVID pandemic in 2020. Since then, the crisis has deepened, attracting national attention and resources. In addition to being exposed to student trauma and anxiety every day, many educators also are working through their own struggles, severely testing their ability to cope.

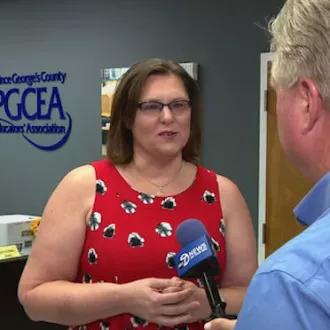

Donna Christy, president of the Prince George's County Educators' Association, in Maryland, worries that even as school leaders and policymakers acknowledge the challenges facing educators, they may not grasp the urgency.

“Our educators are not equipped right now to do what needs to be done—to be the caring, compassionate, supportive educators they want to be,” Christy says.

Compassion fatigue causes burnout—and that leads to educators leaving the profession. Resulting staff shortages exacerbate already crushing workloads and caseloads, leading to even more departures.

“Right now, we’re in a bit of a downward spiral," says Christy. "And we must figure out a way to get on the other side and reverse this.”

What is Compassion Fatigue?

In the mid-1990s, American psychologist C.F. Figley defined compassion fatigue as a “state of exhaustion and dysfunction—biologically, psychologically, and socially—as a result of prolonged exposure to companion stress.” Compassion fatigue, Figley said, was the “cost of caring." Common symptoms are fatigue, loss of interest in helping others, and heightened feelings of hopelessness.

Until recently, the discussion around compassion fatigue focused on mental health professionals, first-responders, nurses, and other professionals dedicated to the relief of individual emotional and physical suffering.

Over the past few years, researchers began to include teachers in their surveys and analysis. With nearly half of U.S. children having experienced adverse childhood events, poverty and trauma, how could educators, in their supportive role, not be affected? Overall, the available research indicates that compassion fatigue among teachers is prevalent and disproportionately impacts those in underserved schools.

Another condition that has gained prominence and is often conflated with compassion fatigue is “secondary traumatic stress” (STS), or "vicarious trauma." While the two are very similar, STS is more of a component—a rather urgent one—of compassion fatigue.

“Compassion fatigue generally sets in over time, hence the 'fatigue,'” explains Steve Hydon, a clinical professor at the University of Southern California. “Secondary traumatic stress can set in almost immediately because of a student experience.”

A 2012 study by the University of Montana found an increased risk for STS in school personnel. Analyzing over 300 staff members in six schools in the northwest United States, researchers found that “approximately 75 percent of the sample exceeded cut-offs on all three subscales of STS. Furthermore, 35.3 percent of participants reported at least moderate symptoms of depression.”

However, unlike other professionals, teachers and school staff members aren't trained to navigate the emotional toll brought about by compassion fatigue and similar phenomena, leaving them particularly vulnerable. This was an issue before the pandemic and has only been exacerbated since, says LaVasha Murdoch of the Washington Education Association.

As a UniServ director (an NEA staff member who supports the state and local union and individual union members), Murdoch routinely heard from WEA members during the pandemic about the mental health struggles they were enduring. “Some of our educators are still not ok," she says. "We need to be looking at secondary trauma. We need more acknowledgement that the same issues that are kids have been dealing with, so have our teachers, our bus drivers, and our counselors.”

“It Just Sneaks Up on You”

When the often-debilitating effects of compassion fatigue take hold, teachers and other staff can be caught off-guard.

“The problem is you don't see it in yourself, and it's sometimes hard to be self-reflective and be able to identify what's going on,” says Christy, a school psychologist. “It happens a little at a time so that it sneaks up on you.”

Even though school counselors are not trained to be mental health professionals, they are often expected to perform as one, particularly when districts look to cut social workers and psychologists. As caseloads rise, counselors often find themselves pushed to the brink. "And then, we're just told to handle it," says Manganaro.

As compassion fatigue took its toll, Manganaro changed course. She returned to teaching art (where she began her education career).

She also went back to school and, in 2023, completed her dissertation on compassion fatigue and school counselors.

“There was a gap in the research specifically around school counselors, so I wanted to highlight not only the causes but also the lack of resources or training," Manganaro explains. "I feel fortunate because I was able to return to the classroom, make a transition to another position. But others are not so lucky. They don't feel supported and will just leave altogether.”

Quote byDonna Christy, President, Prince George's County Educators' Association

No One Answer

Manganaro practiced self-care and found support from friends and colleagues. But ultimately, she says, schools need to prioritize professional development, hire more staff, and reduce caseloads.

For her dissertation, Manganaro interviewed ten school counselors in Arizona who were experiencing symptoms of compassion fatigue. They told her that “difficult student issues and lack of institutional support”—not personal attributes and work/life balance issues— were driving their compassion fatigue.

That’s the core issue, says Sherry Pineau Brown, a lecturer and coordinator of teacher education at Colby College, in Maine, because too many educators work in unduly stressful conditions.

“The heart of healthy communities are healthy schools, right? And we need healthy adults working within those schools to help our kids because we know they're not healthy,” Brown explains.

A former high school teacher, Brown says that while education is a "caring profession," and there is a deeper purpose for those teach, “educators are not martyrs."

In 2023, Brown and Catherine Biddle of the University of Maine released a study examining the “cost to caring” (in the form of compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress and burnout) and potential remedies to mitigate the harm to teachers. Interviewing 540 Maine teachers, Brown and Biddle found that the levels of STS and burnout were very much in line with professions such as nurses and first-responders.

They also concluded that personal resilience and “compassion satisfaction” (the satisfaction derived from being a successful teacher) is helpful in mitigating burnout.

But it starts with a positive school climate.

Brown urges school systems to amplify teacher voice and expertise and not resort to “toxic positivity” and “cutesy wellness.”

A system-wide approach can help neutralize, or at least mitigate, those factors that can turn compassion fatigue, STS and similar conditions into the backbreakers they often are.

“There is no one answer, and we need lawmakers and the general public to understand that our members are being asked to cope with toxic situations in their schools,” says Christy.

In Prince George's County, Christy says the union has been instrumental in providing a venue for support systems. “We all need those spaces and opportunities to unload and talk about what's going on, be able to ask, ‘Where do you need help?’"

But the time for temporary “Band-Aid” solutions is over. Mental health days for educators, for example, are fine, but are "not the answer," says Christy. Research shows that school leaders who protect teachers’ time, invite their input, and support their mental health and well-being through comprehensive programs see higher levels of satisfaction.

This is where educators and their unions have focused their advocacy since staff shortages—before and after the pandemic—have destabilized entire school districts.

“The focus is always going to be on students,” Christy says. “So lawmakers and the public have to understand how everything is connected. You can't leave educators out of the conversation about mental health. We’re letting everyone know, we can’t take care of your kids unless we take care of ourselves, and we need help doing that.”

Suggested Further Reading

-

Ways to Wellness: Compassion Fatigue: A Systemic Concern

California Teachers Association

-

Tackling Compassion Fatigue in Education

Grand Canyon University

-

The Impact of Secondary Trauma on Educators

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

-

When Students Are Traumatized, Teachers Are Too

Edutopia